My easy-to-understand write-up on the Adani fiasco

If you’re a company that’s accused of fraud, it’s usually bad for your company’s investors. Depending on the size of the fraud, you’d be fined a lot of money and it’s ultimately your investors who would pay. On the other hand, if you’re a company that’s accused of fraud, and one of those accusations is of being on the receiving end of government “leniency”, it’s usually good for your investors. If the government is friends with your company, your investors will actually make more money and be very happy.

Of course, if you’re a nefarious company constantly being accused of fraud, sometimes you might just defraud your own investors. This is obviously bad for your investors, because you’d be stealing from them.

My larger point is that an accusation of fraud—by itself—isn’t enough for investors to think less of your company. If you’re defrauding the government, banks, your customers, or the public at large, that’s fine! But if you’re defrauding your investors, that’s a problem.

Ten days ago, the narrative around Adani Group was that they’re doing well because the government likes them. Banks kept giving them money, the government kept giving them contracts, etc. etc. and that was good for business. Adani is “close to Modi” foreign publications would write—and that’s good for business!

Last week, though, Hindenburg Research, an American short-selling firm, accused the Adani Group of not just defrauding the government, banks, etc. but also its investors. I’d alluded to this when I wrote about why Adani stocks only go up:

One way to bypass all of the regulator’s BS is to just pay someone else to buy up your shares and hold on to them. You would then own about 75% of the company, ~20% would be with the entity that you paid, and the remaining 5% is what would actually be traded on the markets.

This is not a liquid stock. You might be the largest marble manufacturer in the world, and marbles might be the next hot obsession of crypto bros who would be minting NFTs on your marbles, and you might have billions in revenue, but a stock which has only a small number of shares that can be traded on the market is not liquid. There will be situations where the buyers have to “convince” the sellers to sell, pushing the price up significantly every time. Over time, these pushes and nudges can amount to a lot and might even make you the (second) richest person on the planet.

Entirely coincidentally, India’s gem Gautam Adani recently became the second richest person in the world, and a lot of his companies have very few shares trading on the market.

If you own most of the shares of your company, you’re artificially increasing its demand and consequently its price. You’re defrauding your investors by falsely inflating the price of your stock. [1] In Adani’s case, I implied that the Mauritius-based funds that owned large parts of his companies’ stock were likely controlled by him. Well, Hindenburg gathered a bit of evidence [2] by speaking to former employees of one of the Mauritius-based funds who confirmed the whole thing:

The former trader said it was obvious Elara’s India Opportunities and Vespera funds belonged to the Adani Group, citing the ownership concentration:

“The answer to your question lies on, like, a fund, for example Elara India [Opportunities Fund], what [are] its concentrated holding[s]? So what are its top ten value [of] holdings? So you would come to know who controls this fund, which conglomerate controls this fund. It’s very simple.”

As explained above, around 99% of Elara India Opportunities is comprised of Adani stock, and previously in June 2022, 93.9% of Vespera was invested in Adani Enterprises:

“The picture is right there, you know. It’s like staring in your face. It is just [that] somebody needs an audacity to kind of put it down on a piece of paper and you know just get it out. Because it´s right out there. You can see that, okay, but does somebody have the courage or the balls to really put it out there?”

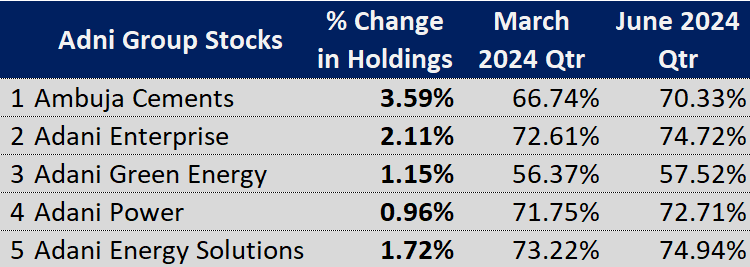

The stock prices of all Adani Group companies have fallen through the last 7 days, since Hindenburg’s report came out, some by nearly 50%. But it wasn’t fraud that was the problem—the problem was that it was fraud against its own investors.

The successful offer

If you’re a publicly-listed company looking to raise money by selling stock, the way to go about doing this is by pricing the stock that you’re selling less than the price of the stock available on the stock exchange. If you price your stock more than the market price, investors who want to buy your stock have no reason to buy the stock from you and can just buy it from other investors on the market.

Adani Enterprises, one of Adani Group’s companies, was looking to sell its stock at a 10-15% discount to the market price. Then its stock price fell thanks to Hindenburg and it ended up selling the stock at a 10-15% premium to the market price (the stock’s even further down now). Investors committed to buying stock from Adani at a price higher than what they could get right away in the market!

From an efficient markets point of view, this was totally bizarre. If an investor has a choice to buy the same stock for a high price as well as a low(er) price, she should buy it at the lower price, every time.

When news first came out that Adani had succeeded in selling stock at a price higher than market price, there was a lot of head scratching. Then reports came out that other Indian billionaires including Sunil Mittal and Sajjan Jindal had bought those shares with their own cash, while retail investors (like you and me) and mutual funds had stayed away.

That makes sense! If you’re a company selling to random small investors, mutual funds, pension funds, etc. what’s most important for those investors is that they get a good price for your stock, certainly below the market price. That’s the entire point of them buying from you. But if you’re selling to your friends, the price is maybe not so important. You could imagine Adani calling up his billionaire friends and saying, “Bro, can you please put in a couple thousand crores into my stock, I’ll owe you one,” and the billionaire friends reluctantly following through because a friend in need is a friend indeed?

The reason this stock-sale (called the “FPO” or follow-on public offering) was important for Adani was:

- Adani’s companies were owned almost entirely by Adani or shady Mauritius funds (allegedly) controlled by him. If he or his investors wanted to sell stock in the future, he would need retail investors and mutual funds to buy

- It’s a big prestige issue! “When I sell, investors buy,” is a powerful statement to the world

When Adani’s billionaire friends bought his stock almost as a favour, point (1) was out the window. But (2) would still hold up*.* Adani had succeeded in selling stock, just not to the investors he was looking for. [3]

The unsuccessful offer

Last night, Adani Enterprises called off its public stock offering, and decided to return all the cash that investors had committed. After probably days of pursuing investors, when investors finally bought Adani stock, why return it?

If you’re a company selling a large amount of stock, you might worry that you might be selling too much stock and that investors wouldn’t have the money to actually pay for it, even if they would want to. The way around this is to either:

- Sell less stock, only as much as investors can actually afford to pay

- Sell the same amount of stock, but collect half of the money now, and half later

Option (1) is boring because then the company won’t actually get all the money it wants. Option (2) is nicer, for the company at least.

If you’re an investor, though, there is an apparent risk. If you pay ₹50 to buy a share worth ₹100, you’re “reserving” the full share for half the price. Later, when the company asks for the remaining ₹50, if the share price is around ₹100 (or more), all good! You’ll pay ₹50 and convert your half-share to a full-share. But if the share price has fallen to, say, ₹40, it’s a problem. Now you as the investor have two options:

- Pay ₹50 to convert your half-share into full

- Lose your initial investment of ₹50, take the loss and move on. (If you really want to, you can buy the stock at ₹40 from the market)

Option (1) is just stupid. (2) is the only rational thing to do. [4]

Adani Enterprises, in this public offering, was to issue partly-paid shares to its investors, just like I described above. Investors committed to buying its shares at ₹3,112 each by paying half, that is, ₹1,556. They had overpaid to begin with, and yesterday, the share price fell another 30% to ₹2,179.

You see the problem here? If the stock price falls another 30% and goes below ₹1556, these investors in the future would face the awkward choice of either losing 100% of their initial investment or doing Adani a second favour and overpaying for its stock. Again!

One could imagine a situation where anonymous, innocent small investors would buy Adani stock in its public offering and then lose their initial investment entirely because the stock fell a bit too much. But if these investors are your own friends who did you a favour in the first place—you don’t want their investment to go to zero and would rather give them back their money.

Footnotes

[1] The fraud here is more against the company’s future investors who might end up buying your stock at intentionally high prices, rather than its current investors who would love if your stock price went up.

[2] Hindenburg obviously has dug into this a lot more and Finshots does a great job of summarising and simplifying all of Hindenburg’s allegations and Adani’s responses here. Most of the firm’s allegations are actually based on public information from Adani Group’s own disclosures.

[3] Yesterday, a Forbes article titled “There’s Evidence That The Adani Group Likely Bought Into Its Own $2.5 Billion Share Sale” suggested that Adani Group bought its own stock in its stock offering. I find the evidence unconvincing. The report has a great catch in that one of the underwriting banks, Elara Capital, is associated with one of the shady Mauritius-based funds that hold Adani stock, Elara India Opportunities Fund. This should probably not have been allowed by SEBI—underwriting banks shouldn’t be having a conflict of interest—but it’s a massive jump to say there was evidence for Adani buying into his own FPO.

[4] A partly-paid share is essentially a call option for the investor. If the share price falls by 50%, the investor loses 100% of their investment.