Part 2: Belief Calibration

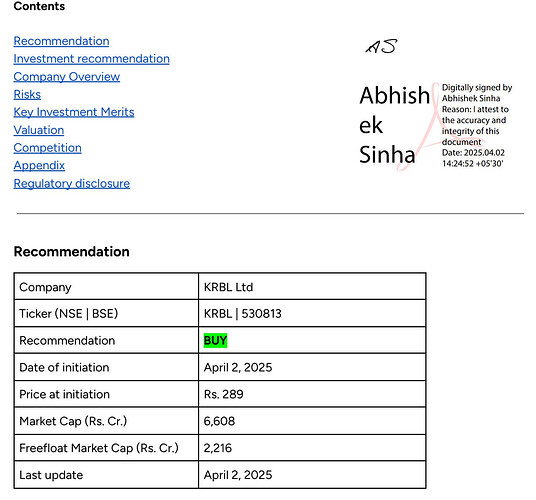

My thesis seemed to be playing out. The company had returned to growth after struggling for 2-3 years. I had been studying this business for over two years. Convinced by the quality and resilience of the business model, I kept buying. It became my largest holding.

The Icing

Management disclosed a large asset monetization plan for their Ghaziabad plant—~150 acres valued at ₹4,000 crore currently, potentially ₹7,500 crore by the time of shift. The plan was to move the plant 50-80 km away near Meerut over 2.5-3 years and develop the Ghaziabad land into a township. They would tie up with a developer. KRBL would retain majority economics.

This made sense. Asset-light value unlock. Let someone else do the heavy lifting.

I was elated. The downside to my base case valuation was now further protected—the company could unlock value from this land bank whenever they wanted.

The Crack

Just when everything seemed to be falling into place, lightning struck again. Albeit, it was caused by internal, rather than an external factor.

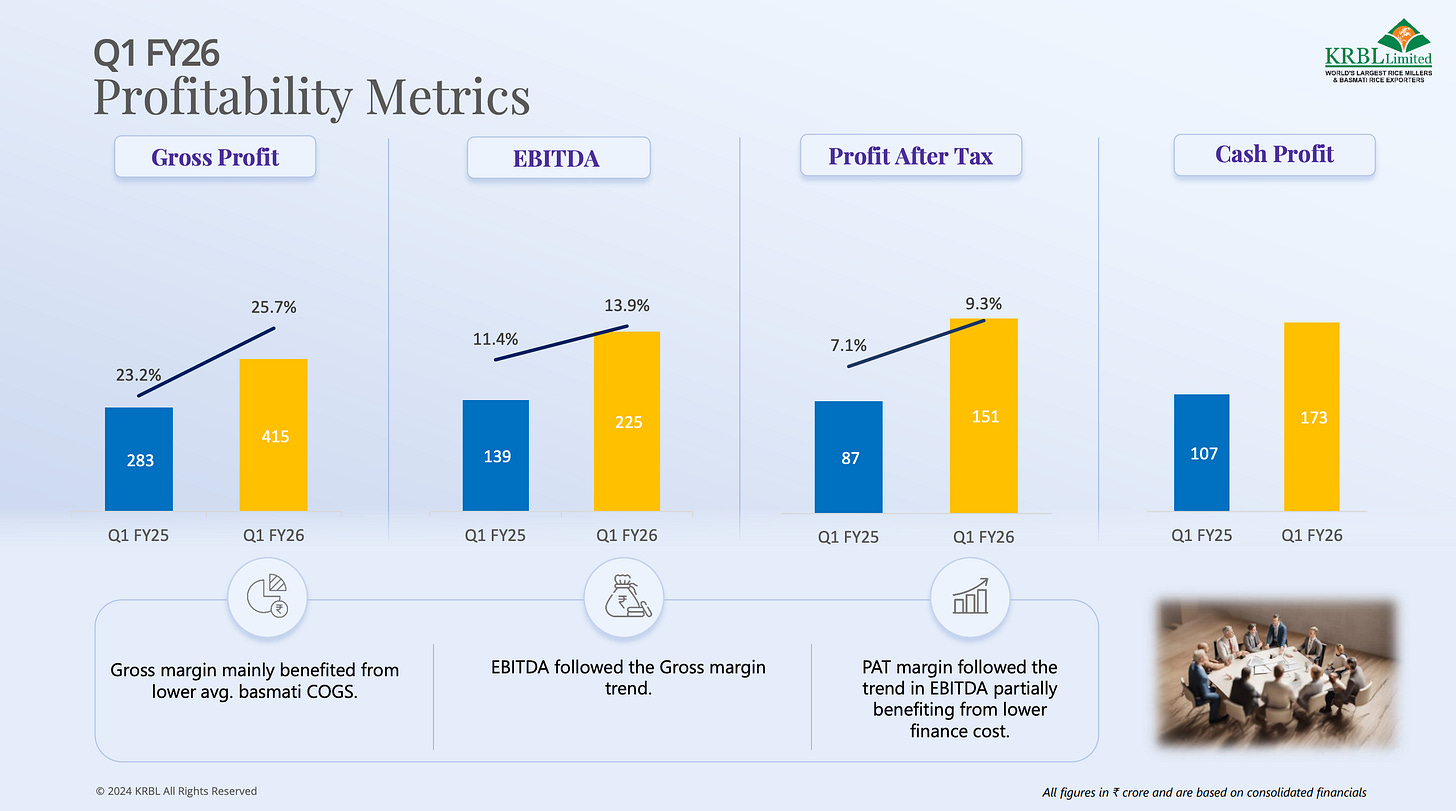

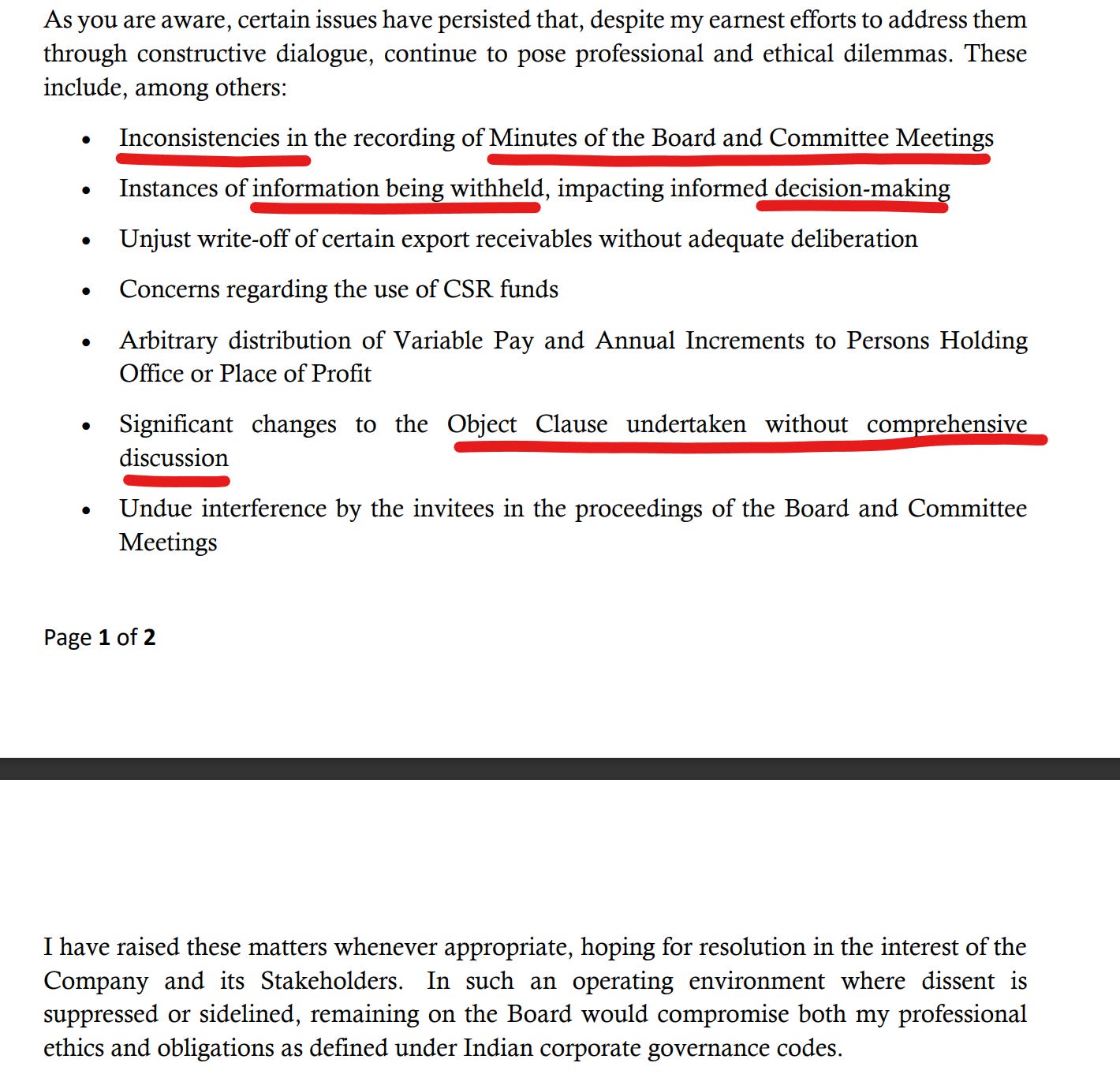

An independent director resigned on September 8. The company disclosed the resignation letter to stock exchanges on September 13—a gap of five days. The letter dropped like a bomb. It cited multiple concerns: inconsistencies in board minutes, information being withheld, unjust write-offs, and an environment where “dissent is suppressed or sidelined.”

Source: Intimation to Stock exchanges

This was unusual. Independent directors rarely cite specific reasons for resignation. The standard template is “personal reasons” or “to pursue other opportunities.” This was neither.

I was nervous. It was a couple of sleepless nights as I tried to ascertain the severity. I spoke to a few fellow investors. The consensus was that this could be a personality clash, or perhaps a disagreement that got out of hand. Don’t read too much into it - this is a business run by Indian promoters. Mediocre governance is already priced in. Anyway, the governance quality advertised in glossy annual reports of most promoter-run firms is mostly overstated. It’s the promoters who call the shots.

The market’s short-term negative reaction was expected. That didn’t worry me. What worried me was the continued cloud over governance. I decided to take it slow. The downside was limited. No need to panic.

The company arranged an investor concall to address concerns. The CMD dismissed the allegations as “all wrong and false.” Suggested the director had become “hostile.”

Subsequently, they announced that AZB & Partners—a reputed law firm—would conduct an independent review of board practices.

I wanted to give management the benefit of doubt. The business fundamentals were strong. Stay focused on what matters.

The Turn

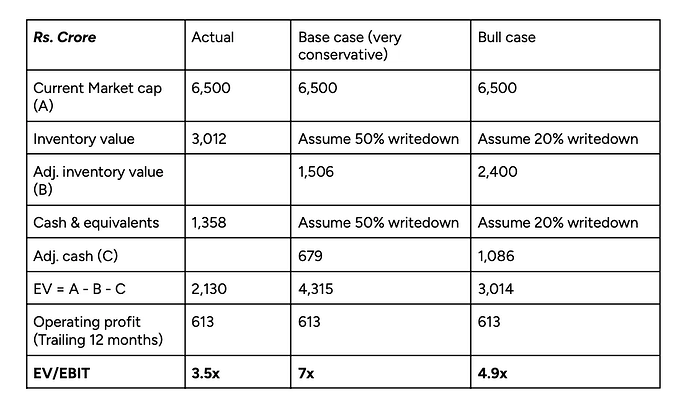

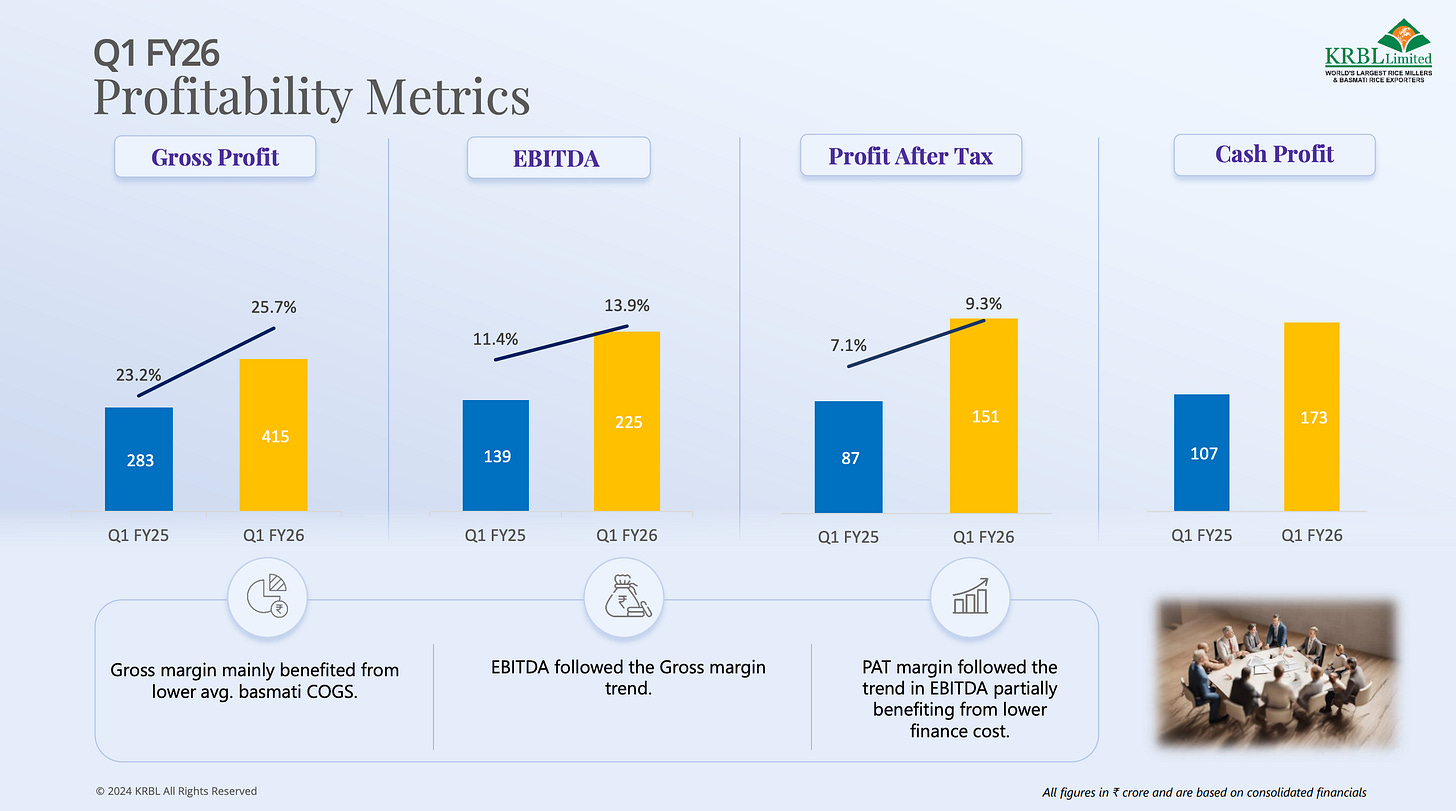

KRBL delivered a solid performance in the Q2 FY26. Income up 18%, Gross margin improved by over 5 percentage points. Inventory situation improved - resulting in cash and equivalents of over Rs. 2,000 Crore.

But buried in the CMD’s opening remarks was a horror story in the making:

“Built on our strong financial position and healthy internal accruals, KRBL is now set to enter the real estate sector as a strategic step towards long-term value creation.”

They announced that they have acquired a land parcel through NCLT at a distressed valuation. They plan to trade Rs. 1,000+ crore of such assets over the next 3-4 years.

In August, the story was that we would monetize the factory land, that’s it. That story lasted just three months.

An investor asked the obvious: “If funds aren’t utilized well, return cash to shareholders through dividends. They can invest in real estate companies themselves.”

The rationale of not returning cash to shareholders? Dividends and buybacks are not tax-efficient.

The company has been reluctant to return cash via dividends. KRBL had massive headroom for FMCG growth - making tuck-in acquisitions in adjacent categories or returning surplus cash through buybacks. Even failed FMCG acquisitions would have been better; at least the market would value the company as a consumer business with growth optionality.

₹2,100 crore in cash. Market cap ~₹9,000 crore.

Imagine if management had announced a ₹500 crore special dividend, a ₹300 crore buyback at depressed prices, ₹200 crore for strategic FMCG acquisitions.

Same ₹1,000 crore outflow.

But the stock could possibly have re-rated. If market cap reached ₹15,000 crore (still at discount to its peers in FMCG), the promoters’ 60% stake would be worth ₹3,600 crore more.

Everyone wins.

Instead, they chose to deploy cash into a business where they have no competitive advantage, returns are uncertain, and the market will apply a conglomerate discount.

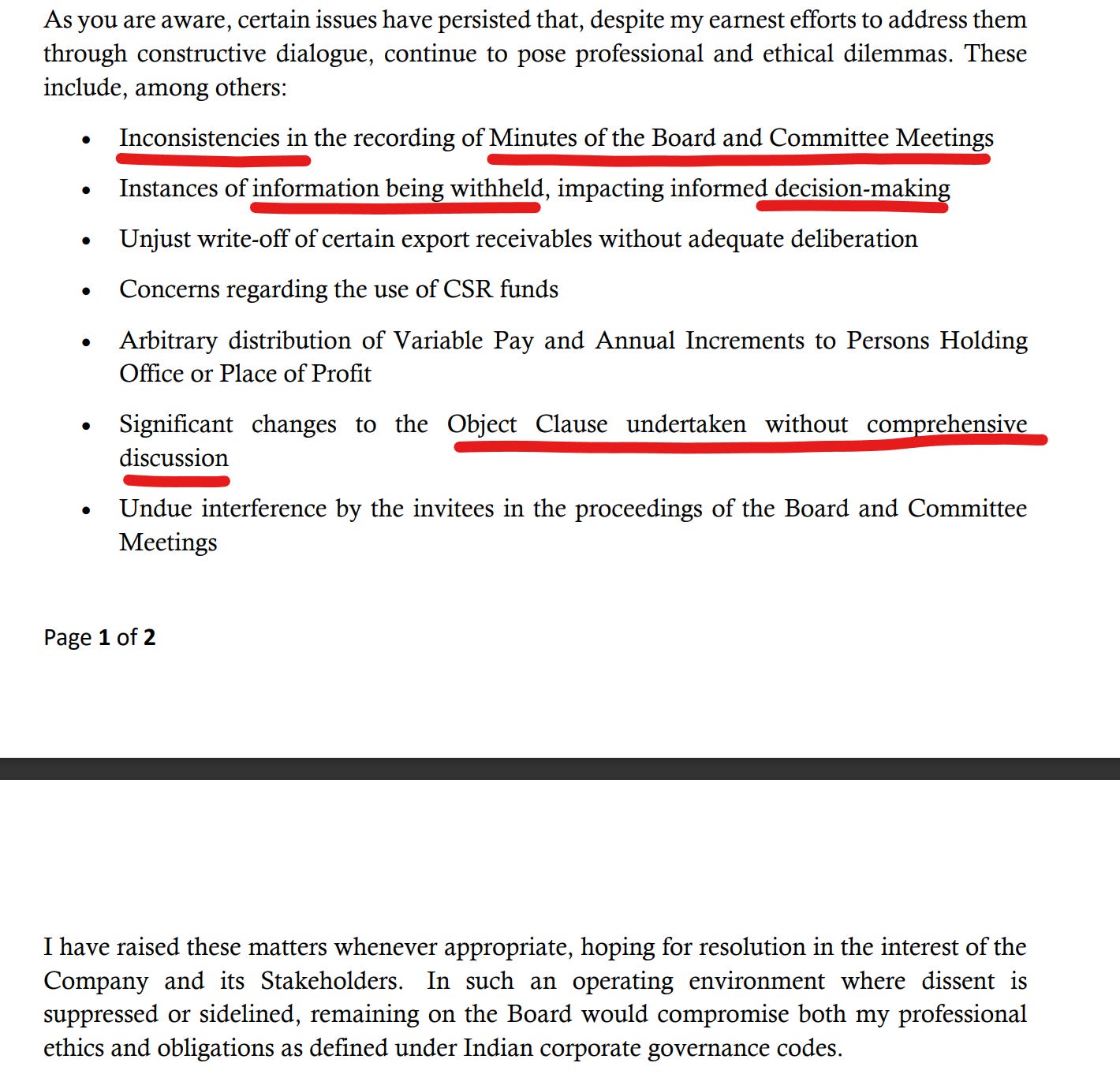

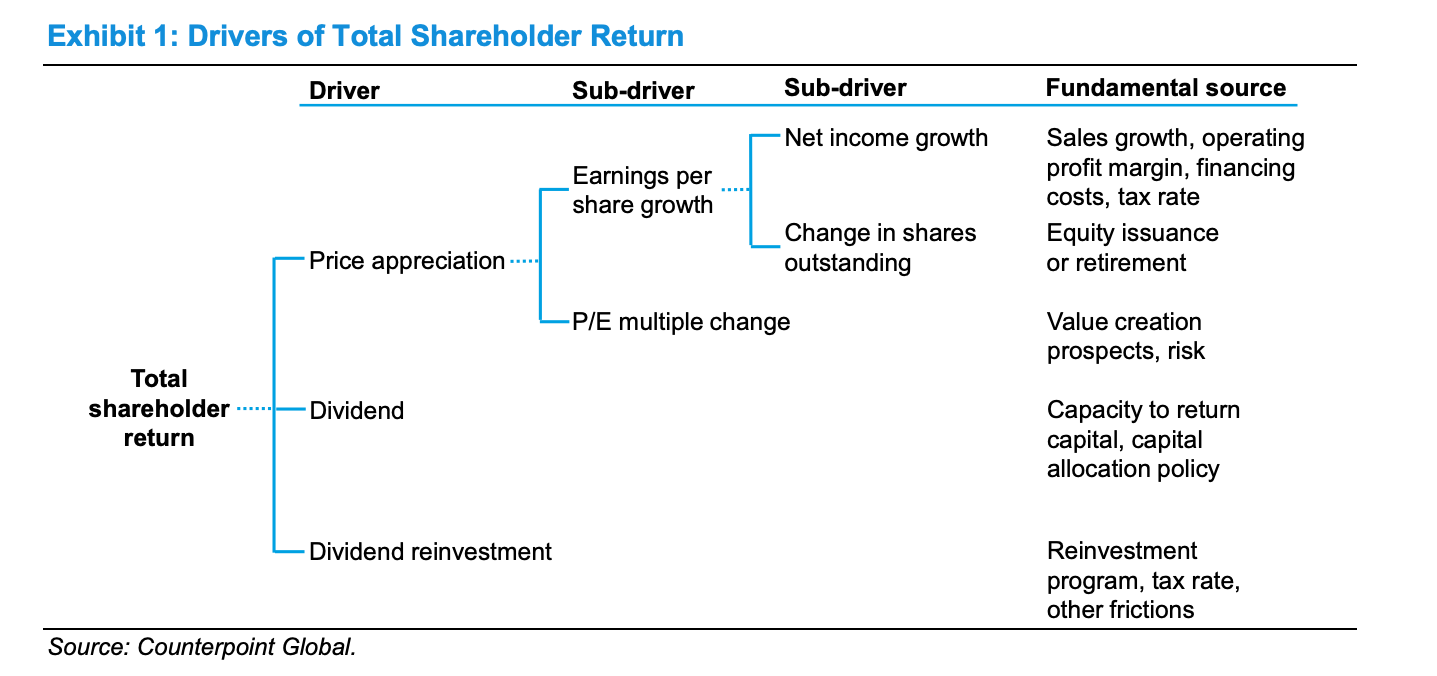

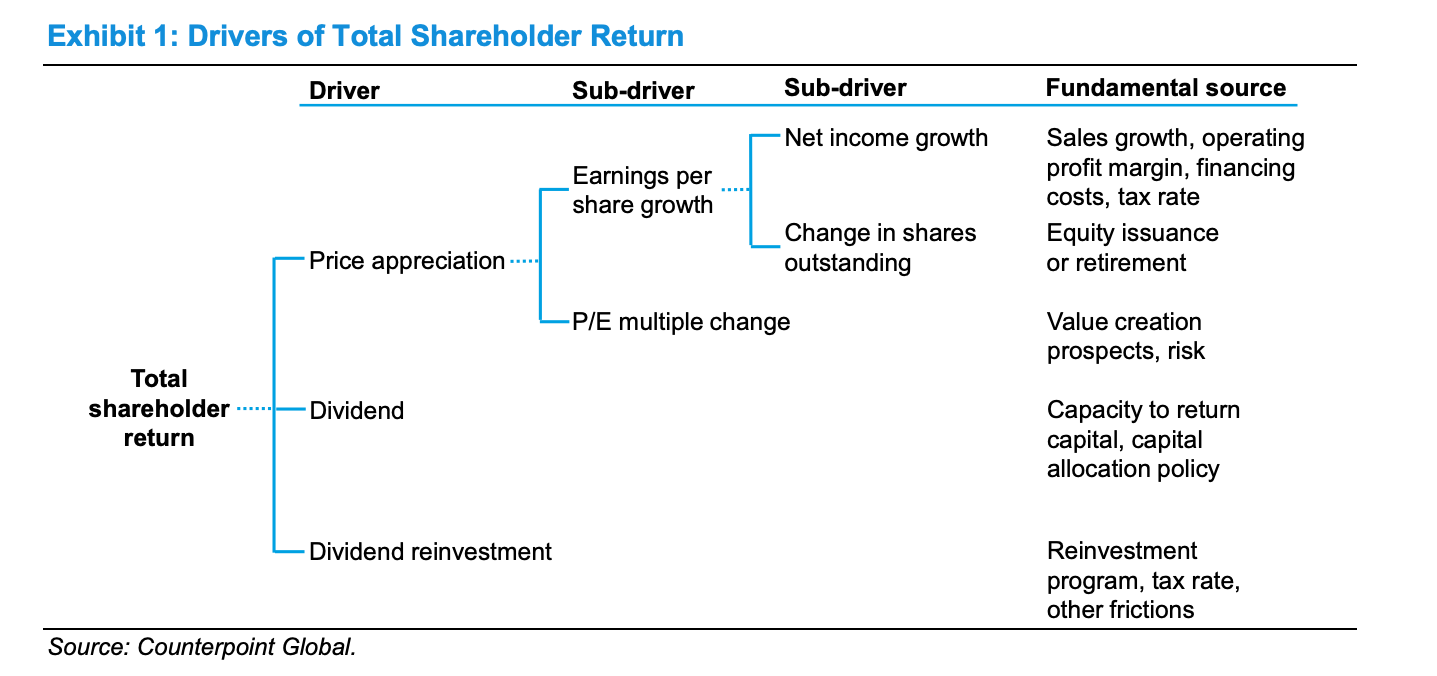

Investing 101: What Drives Shareholder Returns

Source: CounterPoint Global / MS

Putting this in simple equation

Price = Earnings × Multiple (aka PE or PB or PS ratio)

P = E × M

Therefore, price return decomposes into:

ΔP/P ≈ ΔE/E + ΔM/M

Price Return ≈ Earnings Growth + Multiple Change (Re-rating)

Minority Shareholder Value Creation

Value Creation = Price Appreciation + Capital Returns

Value Creation = (Earnings Growth + Re-rating) + (Dividends + Buybacks)

The KRBL Problem

For significant re-rating (ΔM > 0) in this case, we would need institutional capital flowing in. But institutions are unlikely to allocate to companies where management isn’t aligned with them.

Which means:

Value Creation = Earnings Growth + 0 + 0

↑ ↑ ↑

(business) (re-rating) (capital returns)

KRBL delivered earnings growth. But without re-rating AND without capital returns, minority shareholders are left holding a business that compounds intrinsic value that they can never extract.

The Structure Problem

Promoter-backed companies have created enormous wealth in India. But there are many horror stories of poor capital allocation and minority shareholder treatment.

The issue isn’t promoter ownership—it’s concentrated power without adequate checks.

In a recent episode of Everything is Everything , the hosts make a simple observation: when power is concentrated in one person, the quality of decisions is generally inferior.

Good decisions require disagreement, many minds, checks and balances.

A dominant shareholder doesn’t have these constraints. More damning: “How do we make sure that 40% minority shareholders get 40% of the cash?” They call this a pervasive problem in how many Indian firm works.

The dominant shareholder often extracts more than their proportionate share of value—not through fraud, but through capital allocation choices that prioritize family interests over minority returns.

KRBL’s real estate move isn’t unusual. It’s structural. The incentives of a 60% owner are not the incentives of a 40% minority holder. I should have weighted this more heavily from the start.

In one of the interviews, promoter’s son sang praises of Harsh Mariwala and said they want to build an organization like Marico.

Marico has razor focus on capitalizing their core strengths. Marico returns cash to shareholders. Makes strategic acquisitions within their competence. Doesn’t become a real estate developer because treasury yields are low.

The Tuition

Being contrarian for the sake of being contrarian is stupid. Some businesses deserve cheap valuations - not because the market is wrong about the business, but because the market is pricing in something else correctly; management behavior in this case.

Just because it’s listed doesn’t mean it’s investible. A stock can have excellent fundamentals and still be a poor investment if there’s no pathway for value realization. This deserves a separate piece that I intend to write about soon.

There is a distinct difference between a lifestyle business and a professionally run company. In a lifestyle business, the company exists to support the family. In a professionally run company, management exists to create value for all shareholders. KRBL’s actions reveal which category they belong to.

When facts change, update the probabilities. I had an investment thesis with multiple catalysts. When the independent director resigned citing governance concerns, that was new information - the probability of management alignment shifted downward. When management announced real estate diversification, that was decisive information - the thesis became invalid. Waiting for certainty is a mistake. Each new piece of information should update your view, not get rationalized away.

Watch what they do, not what they say. Admiring Harsh Mariwala means nothing. Acting like him means everything.

The Exit

I am learning to define a clear exit/trim criteria for every position I buy. Not price targets. The criteria based on what would make the thesis invalid.

For KRBL, diversification into unrelated businesses was an exit criterion. When management announced ₹1,000 crore into real estate, the criterion was hit.

So I exited.

Not because the business deteriorated. The business is fine. Possibly better than fine. Basmati rice consumption in India has long way to go. KRBL’s competitive position is intact.

That’s not my concern anymore.

I was lucky to exit with modest gains - the thesis worked long enough for the stock to re-rate partially before management revealed their hand. Not every mistake gives you this grace period.

When an exit/trim criterion is triggered, you exit/trim. No renegotiation. No “let me see how this plays out.” No attachment to the meticulousness of your original thesis. A four-legged stool with one broken leg can stand, but is structurally weak. I don’t keep it.

Liked this post? Share it with a friend.

This is not about maximizing returns. It’s about sleeping well . It’s about having a process that doesn’t require me to be right about things I cannot control - like whether a consumer goods co. will suddenly decide to become real estate developers.

I’d rather miss upside I can’t back than stay in a position where my original reasoning no longer applies. That’s not discipline - that’s hoping. And hope is not an investment strategy.

The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.

But sometimes, the opposite of a good idea is a bad idea for the right reasons.