Continuing this conversation here, because this thread is more relevant.

One of my biggest pet peeves when it comes to the topic of valuation (Especially in the context of Indian Equities) is that people who defend astronomical valuations in ‘Quality companies’ almost always quote terrible, questionable and/or companies with poor economics as the antithesis.

I would like to argue vehemently that whenever someone (Well, at least me personally) points out that XYZ company is overvalued, we not saying that the alternative approach is buying any company below 10 P/E. That is not how valuations work.

Here’s my 2 cents on this topic. This was posted as an answer on Quora first. But I will re-post it here because sometimes Quora answers get taken down for weird reasons.

The Parimutuel System as Explained by Charlie Munger

A prominent question many people have about investing in stocks is, “Does the purchase price matter?” or “Should I value a stock before purchasing it”?

Financial theory argues that you shouldn’t. They say, markets are always efficient in pricing securities and you should rather worry about decreasing frictional costs like brokerage charges, transaction charges, churn costs and so on. But Mr. Charlie Munger, the business partner of the world’s richest investor Mr. Warren Buffett, has a different answer:

“ It was always clear to me that the stock market couldn’t be perfectly efficient, because, as a teenager, I’d been to the racetrack in Omaha where they had the pari-mutuel system. And it was quite obvious to me that if the ‘house take’, the croupier’s take, was seventeen percent, some people consistently lost a lot less than seventeen percent of all their bets, and other people consistently lost more than seventeen percent of all their bets.

So the pari-mutuel system in Omaha had no perfect efficiency. And so I didn’t accept the argument that the stock market was always perfectly efficient in creating rational prices. The stock market is the same way – except that the house handle is so much lower.

If you take transaction costs – the spread between the bid and the ask plus the commissions – and if you don’t trade too actively, you’re talking about fairly low transaction costs. So that, with enough fanaticism and enough discipline, some of the shrewd people are going to get way better results than average in the nature of things.

It is not a bit easy…But some people will have an advantage. And in a fairly low transaction cost operation, they will get better than average results in stock picking. To us, investing is the equivalent of going out and betting against the pari-mutuel system. We look for a horse with one chance in two of winning and which pays you three to one. You’re looking for a mispriced gamble. That’s what investing is. And you have to know enough to know whether the gamble is mispriced. That’s value investing. ”

— Charlie Munger (USCB, 2003).

Interesting. So, what’s ‘Parimutuel Betting‘?

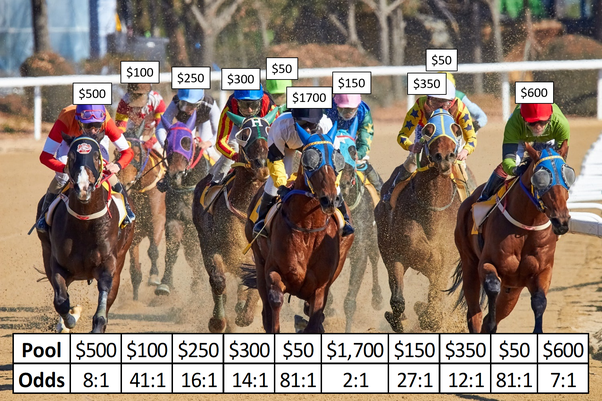

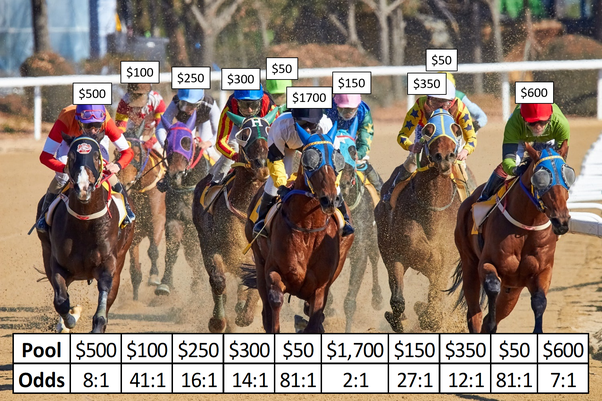

Let’s say that you are about to bet $100 on a Horse Race. A total of ten horses are participating in the race and you are given the following statistics:

You are told that 100 people have laid down their bets (Let’s call them the ‘Horse Market’) and the total pool of bets is $4,050. Indirectly, you can assess how these 100 people have determined the probability of winning, or ‘Odds’ of winning, for each of these horses. In fact, Horse #6 seems to be an overwhelming favorite, with $1,700 bet for the horse.

But before blindly betting on Horse #6, you need to understand the most important thing about Parimutuel Betting. If Horse #6 indeed wins, everyone who bet on Horse #6 will get $4,050 i.e. Everyone will make roughly 2 times of their bet amount (For convenience, let’s just say the remaining 0.38 times is participation fee). Is that good?

Hold your horses (Pun intended)!

If you bet on Horse #5 or Horse #9 instead, you can make 81 times the money, instead of the paltry 2 times. Well, well, now is this a better bet? Logically speaking, these horses have had a very little bet on them because they may be poor to begin with. The 100 gamblers already know this. That’s why only 1-2 of them have placed bets for these horses.

Wait, this is confusing. Which horse should I bet on now? Let’s recount the statement made by Mr. Charlie Munger:

“We look for a horse with one chance in two of winning and which pays you three to one. You’re looking for a mispriced gamble.”

A mispriced gamble . That’s where the trick lies. To summarize Mr. Munger’s thought process:

- You shouldn’t bet blindly on Horse #6, because you will only make only 2 times the money, the lowest reward of the lot. Even when Horse #6 can be deemed the healthiest horse with the most skilled jockey, the payout is simply too low.

- You shouldn’t bet blindly on Horses #5 or #9, even though they have an astronomical payout of 81 times. It is more likely that Horses #5 or #9 could be sick/weak or their jockeys inexperienced.

- The sweet spot, therefore, is in a bet where you think there’s mispricing i.e. A bet where the ‘Odds’ have been miscalculated by the Horse Market people. Take Horse #1 for instance. The Odds here are 8:1 i.e. The Horse Market people think there’s only a 12.50% (1/8) Probability of this horse winning. If you believe that these Odds are somehow way wrong i.e. If you believe that this horse actually has a 25% (1/4) Probability of winning, then you should consider betting on this one. Of course, you should repeat this exercise for all the horses and figure out which one has the most mispriced Odds and bet on that one.

Sounds simple enough? Horse Betting is decidedly more complex than this. However, it proves to be an interesting lesson in investing. This system of Parimutuel Betting, Mr. Munger argues, also applies to the Stock Market. I would personally visualize it like this:

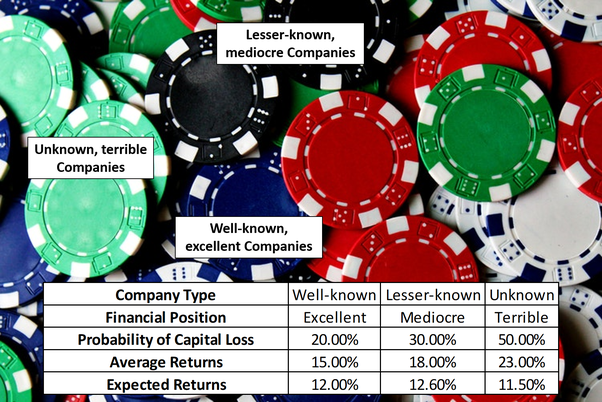

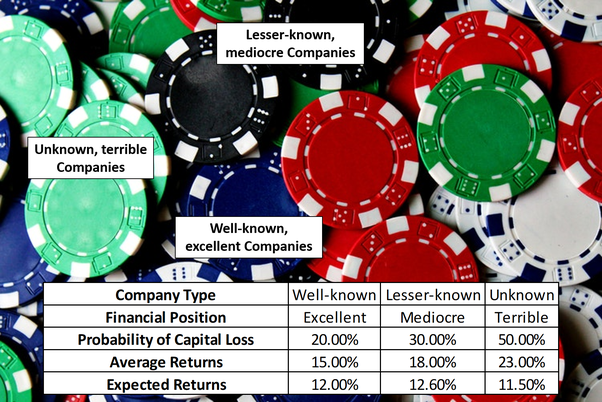

To put it in a words, then:

- You shouldn’t invest blindly in the well-known, excellent company. Although these type of companies have the lowest probability of making a Capital Loss (i.e. Chance of not achieving the Average Returns) over the long term, they also have a low, 15% returns. Put together, they have an Expected Returns of 12%, which is neither too high, nor too low.

- You shouldn’t invest blindly in the unknown, terrible company. Although these type of companies can become potential ‘multi-baggers’ over the long term, clocking a CAGR of 23%, they also come with a high 50% risk of a potential Capital Loss. Put together, they have an Expected Returns of 11.50%, the lowest of the lot.

- The sweet spot, therefore, could be in the lesser-known, mediocre companies. These type of companies offer a decent 18% CAGR over the long term and also come with a moderate, 30% Capital Loss probability. Put together, they have an Expected Returns of 12.60%, the highest of the lot.

Of course, this is just an example and the numbers are all assumed. There are thousands of Stocks listed around the world and there might very well be numerous permutations and combinations of this in action at any given time. Instead of the 100 people from our horse betting example, the Stock Market consists of millions of people. They are pricing the odds for a stock every moment a trade is executed. It is an investor’s job to figure out the most mispriced bet.

Just remember . You don’t make the most money-per-risk-taken by betting on the most favorite gamble. And you don’t make the most money-per-risk-taken by betting on the least favorite gamble, either. You make the most money-per-risk-taken by betting on the gamble where the odds are highly mispriced.